This past month I have been thinking a lot about the peer groups in my life. By peer groups, I mean the primary groups of people with whom I spend time socializing and working. I have spent a considerable amount of time thinking about this because I strongly believe in the law of the average:

You are the average of the five people you spend the most time with. – Jim Rohn

In other words, “one’s peer group is unbelievably influential in one’s development and growth”. And furthermore: “Unlike other agents of socialization, such as family and school, peer groups allow children to escape the direct supervision of adults.”

In the past eighteen months, I’ve identified myself with several peer groups. I’ve seen a lot of people, and I’ve changed peer groups several times. Some peer groups have remained consistent for months in each of my living locations, and others are short-lasted, such as visiting a friend at school on the weekend. Very few people have remained constant throughout, but I am thankful for those that have.

To get an idea of the places I’ve been and the people I’ve spent time with, here’s a short list of peer groups that I considered myself part of for at least a few months:

- Wake Forest student

- Wake Forest rower

- College entrepreneur

- Thiel Fellow

- Silicon Valley resident

- Startup founder

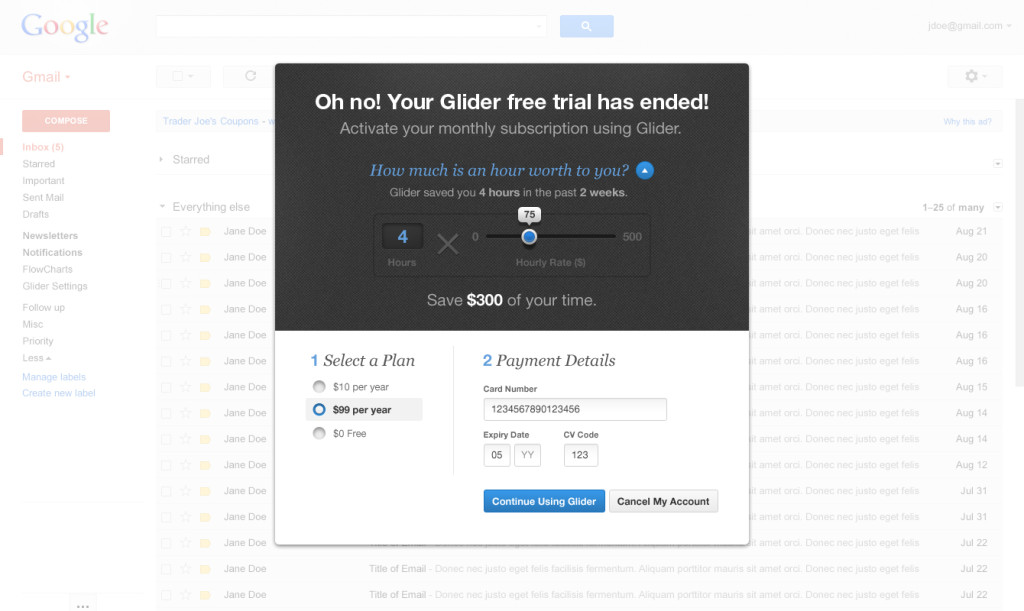

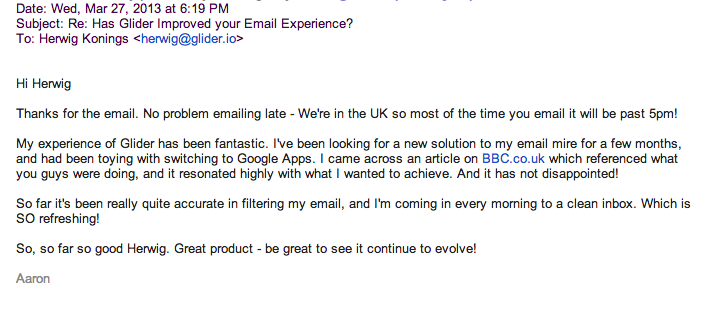

- Founder of Glider

- New York City resident

- College dropout

_

I am not embarrassed to say that creating my own peer group from scratch has been my greatest challenge in the past year. Tougher than recruiting programmers, designers, venture capital, is recruiting a peer group when the overwhelming majority of your peers live within pre-existing communities (college). As someone who is under-21, the toughness is compounded when you live in a social space designed for age 21 and above.

The experience of moving alone to a new region of the country, while working in a small team that stares at computer screens all day, and generally not having many social outlets, is about as sub-optimal as it gets for my personality.

To give you a more specific diagnosis of the peer groups in my life, I turn to a direct excerpt from Tim Madigan in a 2007 issue of Philosophy Now:

In Book VIII of his Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle categorizes three different types of friendship: friendships of utility, friendships of pleasure, and friendships of the good.

Friendships of utility are those where people are on cordial terms primarily because each person benefits from the other in some way. Business partnerships, relationships among co-workers, and classmate connections are examples.

Friendships of pleasure are those where individuals seek out each other’s company because of the joy it brings. Passionate love affairs, people associating with each other due to belonging to the same hobby organization, and fishing buddies fall into this category.

Most important of all are friendships of the good. These are friendships based upon mutual respect, admiration for each other’s virtues, and a strong desire to aid and assist the other person because one recognizes their essential goodness.

The first two types of friendship are relatively fragile. When the purpose for which the relationship is formed somehow changes, then these friendships tend to end. For instance, if the business partnership is dissolved, or if you take another job, or graduate from school, it is more than likely that no ties will be maintained with the former friend of utility. Likewise, once the love affair cools, or you take up a new hobby or give up fishing, the friends of pleasure will go their own ways.

However, friendships of the good tend to be lifelong, are often formed in childhood or adolescence, and will exist so long as the friends continue to remain virtuous in each other’s eyes. To have more than a handful of such friends of the good, Aristotle states, is indeed a fortunate thing. Rare indeed are such friendships, for people of this kind are rare. Or as my mother used to say, “Make new friends but keep the old, for one is silver and the other is gold.” Such friendships of the good require time and intimacy – to truly know people’s finest qualities you must have deep experiences with them, and close connections. “Many a friendship doth want of intercourse destroy,” Aristotle warns us.

And yet, for us living in the frenetic 21st Century, it can be difficult to maintain such ties. Friendships of utility and pleasure come and go quickly as we move from job to job and relationship to relationship. But for Aristotle this need not be a tragedy. Since the interchanges of both types are less intense or permanent, their endings are not necessarily detrimental to one’s self. But to lose a friend of the good – ah, there is tragedy indeed.

The fellowship has been overwhelmingly advantageous for friendships of utility. I stand a lot to gain as a Thiel Fellow, and many of the people who help me with Glider will likely gain quite a bit as well. But remember, these are short lasted because they change quickly with circumstances. Briefly connecting with a lawyer or CEO for advice falls under this category. I also saw myself developing friendships of utility with some of my professors and classmates at Wake Forest.

Friendships of pleasure are particularly challenging to discover outside of the campus environment and this has made me particularly unhappy. These types of relationships were especially strong in college. As a 19-year old it’s hard to find other people who have the freedom of time to do exactly what they want. I can’t blame most of the people who I have sought out in this regard, they enjoy spending time with their friends at school.

Friendships of good will always be challenging to find in any social setting. Fortunately rowing has been a sport where I have developed these relationships in the past, and I carry those relationships from high school. However, without rowing or another organization, finding these relationships has been very difficult. The honest truth is that I spend very little intimate time with the fellows and I believe there may be a lot to gain if we had more informal activity. Outside of rowing, the best target I’ve found for identifying friendships of good are startup founders; a handful of founders have been particularly helpful and inspirational to me on a very personal level.

The Good and the Bad

I would like to highlight one particular instance when my peer groups aligned nearly perfectly. A serendipitous chance weekend this past month. I was able to develop a few relationships of good mainly through Y Combinator friends and the Thiel Fellows over the course of one weekend through deep experiences.

It was a weekend when the majority of my friendships of good happened by chance to all be in NYC at the same time. But it didn’t necessarily start out that way. Over the course of four consecutive days, plenty of deep experience occurred, and friendships of good were formed. A combination of intellectual curiosity, mutual respect, shared ambition, disregard of formal credentials, and an environment which all of us could confide in each other. It was like an elixir.

We spent our days in my office together, casually bouncing thoughts off other entrepreneurs, and our late nights on the bar stools and dance floors of Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

As everyone departed for the weekend, one of my friends sent me a text:

“Something I like… If you’re partying with good/intelligent/driven friends… It doesn’t feel like a distraction, it feels like it inspires me to succeed more.” And “Hah, just don’t do it every weekend.”

Of course these weekends do not happen regularly, but having them once in a blue moon is key to maintaining sanity.

The bad is, well, an incredibly visceral feeling. More so than I can describe in words. It’s the feeling of isolation amongst millions of people in close proximity, and isolation in the sense that you are thousands of miles away from a good friend. For me this has typically been the experience of asking myself on any given Friday night: Who can I hang out with? And the answer being no one, about 25% of the time. Or staring into space as you chow down a burger, another dinner alone at SFO. I would estimate about 90% of my meals are eaten alone. In short, the bad is when you aren’t able to find just one of those five people to make you feel comfortable.

I think college is a place of happy mediums, where it can never get either extremely great or extremely bad. It would be difficult to rally all of your best friendships and all of the people you admire in a single college social setting. But it would also be difficult to feel completely astray from a peer group on a college campus. The “real world” as an entrepreneur typically goes either way to the extremes from my experience. One moment you are spending time with all of the people you absolutely admire, the next moment you are flying solo, just another peson amongst millions of other people.

Going Forward

I am in pursuit of three conditions:

As external conditions change, it becomes tougher to meet the three conditions that sociologists since the 1950s have considered crucial to making close friends: proximity; repeated, unplanned interactions; and a setting that encourages people to let their guard down and confide in each other, said Rebecca G. Adams, a professor of sociology and gerontology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

It’s important to note the results of my good and bad experiences are directly related to my optimization: A small team building software outside of a college campus community. In recent months I’ve started to design my life to create more opportunities for repeated and unplanned interaction.

It really does make the difference when you go to an office and a person you know asks “How are you doing?”. So, finding good friends in a co-working space is a fantastic start. Avoiding hotels when traveling is another great help, financially and socially. Most of all, living in close proximity to friends of good and friends of pleasure is ideal.